This article is an illustrated and resourced summary of “Accessibility”, authored by Thomas Westin, Barrie Ellis, Ian Hamilton, and Eelke Folmer from Mark J.P. Wolf’s “Encyclopedia of Video Games: The Culture, Technology & Art of Gaming” (2021).

In the realm of human-computer interaction, game accessibility pertains to the inclusivity of digital games. Further elaboration on this concept is provided in the subsequent sections.

Barriers

Disability can be defined as a mismatch between a person’s abilities and their goals, often due to environmental or societal barriers. Games, which inherently revolve around overcoming challenges, rely on barriers set by rules. Game accessibility aims to eliminate unnecessary barriers within these rules, allowing a wider range of players to enjoy the game, including disabled gamers. Contrary to misconceptions, making games accessible doesn’t necessarily entail costly or complex efforts; early consideration can lead to cost-effective and straightforward adjustments, benefiting a diverse player base with varied motivations for playing.

The Industry

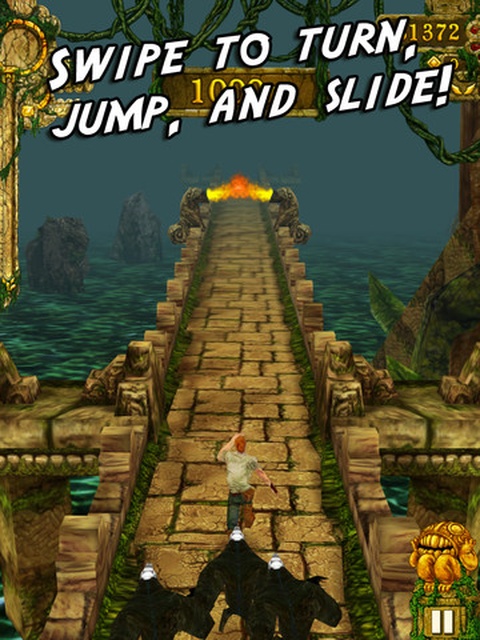

Designing for game accessibility yields a multitude of advantages. This encompasses expanding the customer base for commercial gain, enriching players’ lives by granting them access to cultural experiences and social interaction, and contributing to the broader enhancement of game design. A design tailored for one-handed play benefits not only that specific group but also individuals with a broken arm or those multitasking with a drink in hand (see Figure 1). Similarly, when catering to deaf gamers, it accommodates those playing silently due to a sleeping infant, and a design optimised for low vision enables gameplay even in bright sunlight.

Throughout the evolution of digital games, the game industry has shown persistent efforts towards enhancing game accessibility. For instance, introducing difficulty level settings serves as a universal solution, extending beyond concepts of “easy” and “hard.” Addressing colour-blindness is another recurring accessibility feature.

Despite persisting challenges faced by many disabled individuals in playing existing games, the game industry has witnessed a noticeable transformation over time. This transformation can be attributed to the collective influence of advocacy groups, charitable organizations, and dedicated individuals. A pivotal turning point occurred with the introduction and gradual implementation of the 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act (CVAA) in the United States, starting in 2015 and fully enacted by January 1, 2019. Consequently, interest in accessibility has experienced a substantial surge in industry events.

Strategies

The strategies needed vary depending on the specific game and its design, setting games apart from other industries with more streamlined and similar products. The distinction between necessary and unnecessary barriers is intrinsic to each game due to the uniqueness of its rules. This renders accessibility an optimization process, entailing the identification of the most effective approach for each game by considering potential barriers related to its mode of interaction. Accessibility can by hardware (i.e., Xbox Adaptive Controller: see Figure 2), external software (i.e., screen reader, copilot), and within games (i.e., button remapping, subtitles).

Achieving a positive user experience and accessibility hinges on proactive initial design decisions. Opting against using small text from the outset, for instance, is a design choice. Changing small text to larger sizes during later development involves complex and costly adjustments. Effective tools include adhering to established best practice guidelines (i.e., www.gameaccessibilityguidelines.com, www.accessible.games, www.accessiblegamedesign.com).

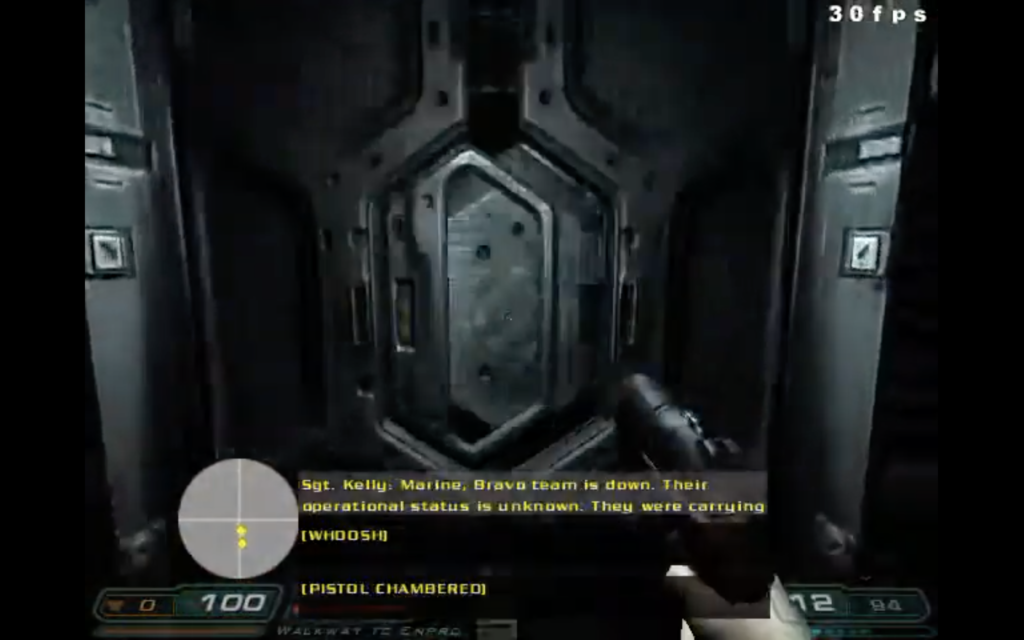

Although retrofitting games is feasible, it often requires both expertise from gamers and external hardware and software, particularly on consoles. Modifications (mods) to game software and hardware are sometimes achievable on PCs. Notable examples include advanced software mods like AudioQuake and Doom3[CC] (see Figure 3) tailored for people who are blind or deaf.

Future of Accessbility

Running parallel to advancements in the game industry and community initiatives, research into game accessibility has been ongoing since the early days of computer games. This exploration encompasses several key categories, with recent research examples including: (1) design tools; (2) development aspects like input/output methods; (3) educational efforts; (4) comprehensive surveys and (5) legal considerations.

Yet, accessibility is not an automatic outcome. The dialogue must persist, and collective efforts must continue: management must exert top-down influence to empower employees, developers with the knowledge and desire to contribute should drive change from the ground up, and the gaming community should voice their desires and needs.

Further Reading

This article is an illustrated and resourced summary of “Accessibility”, authored by Thomas Westin, Barrie Ellis, Ian Hamilton, and Eelke Folmer from Mark J.P. Wolf’s “Encyclopedia of Video Games: The Culture, Technology & Art of Gaming” (2021) and has been copyedited with Chat-GPT 3.5. This article has been written to make Wolf’s Encyclopedia and its entries more accessible.