This brief reflection was written during a seminar on Practical Game Criticism in 2020.

Among the Sleep is a first-person horror adventure from 2014 and was developed by the indie-developer Krillbite Studios with the Norwegian Film Institute’s aid. The game has scored top reviews on Steam also other platforms and remains praised for its concept. Among the Sleep lets the player take the role of a two-year-old kid that traverses a nightmare. The goal is to find his mother.

I am a great fan of Horror videogames, as it is a genre that stays underestimated for being true to what it really means to play. That means in Huizingian terms: running around, not knowing what one is exactly doing, being exhilarated (by fear), playing hide and seek, and having no quantifiable score or skill-based in-game progress; not to speak of one being not distracted by item/equipment fetishism. Among the Sleep provides all those aspects and remains all in all very orthodox to the genre, except for the fact that one plays a two-year-old boy who experiences an extreme nightmare in a Disneyesque graphical style. The concept instantly convinced me while my Freudo-Lacanian expectations were already auto-playing absurd theories in my head. The first two brief sections on the plot and the gameplay intend to set the stage for the actual commentary on the game. These may be omitted if one has already played the game.

Plot

The game starts with introducing you to your POV, which is that of a small child. Everything seems big and hence either intriguing or intimidating. In the beginning, the kid’s mother celebrates his birthday, and one quickly realises that there is no father. The kid is then brought up to his room (Fig. 1) where he is then introduced to a talking bear who was a birthday gift. The mother comes later in to bring the kid to bed. He sleeps, and the real game begins.

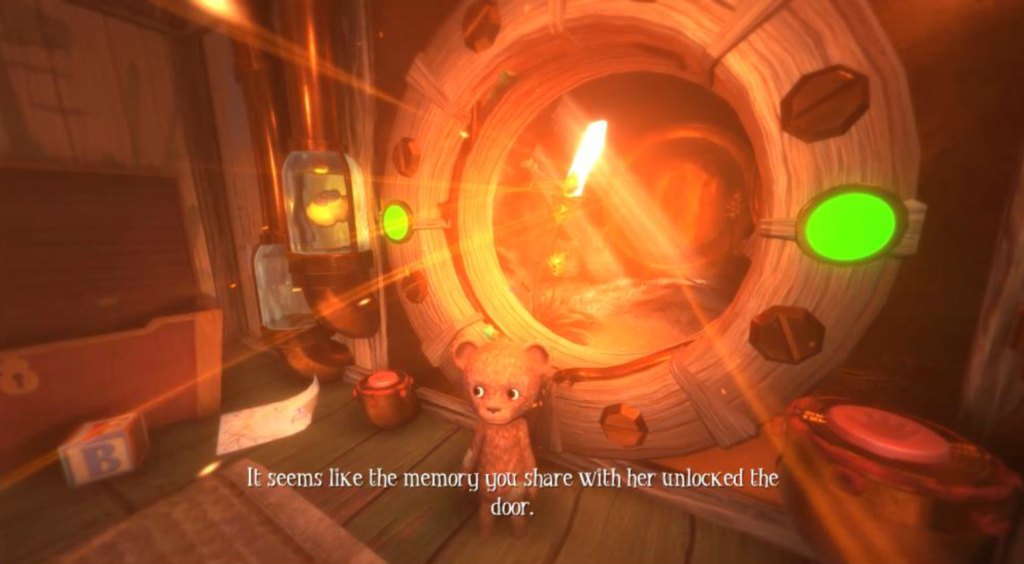

For almost the rest of the game, one encompasses three main levels in which the player must find specific items connected to memories that the child shares with his mother. The game’s operational goal is to find the mother through these memory-items, which altogether can open the final door, which lets the child finally exit the nightmare to find one’s mother.

The first level is an obscure and dark playground (Fig. 2) where a set of owls must be found to open the first memory item’s pathway. The second level is a gloomy swamp in a forest that is entrenched by old wooden furniture and a library at the end. Here one encounters the first monster of the game, a horrifying woman with branches as hair and arms. One must run away and hide from her in order to reach the memory item at the end. The third level plays in a surreal wardrobe labyrinth where one must fear the second monster of the game; the trench coat monster. In the end, we find the last memory item, and after an impressive seen which confronts the child with memories of his mother as an alcoholic, we are brought back into the real world where we find our mother laying drunk in the kitchen. In the end, we can run away and exit the house were suddenly the image blurs into white. The end of the game is the child recognising his father’s voice, who welcomes him with caring words.

Gameplay

The game is story driven, and mechanics are reduced to a minimum. One can walk, sprint, crouch and climb, hold your teddy to glow in the dark and interact with objects (i.e., doors, little objects, keys, etc.). Unfortunately, the game feels a bit clunky because the animations are sometimes inconsistent (I.e., teddy walks through a chair or turns around in one frame) or delayed to one’s control input. Besides, the hitbox of items that can be interacted with is extremely small, so sometimes one needs a couple of seconds to open the door because one has to aim precisely for the doorknob. These aspects make running away or hiding from a monster sometimes unnecessary difficult because one is busy fighting with the controls. Yet, as the game focuses more on the audio-visual atmosphere and narrative that unfolds within the levels, these issues can be endured.

Lacanian commentary

A game that provides a little child’s perspective in search of his mother within his dreams sounds fit for a Lacanian review. Among the Sleep claims to offer a two-year-old’s perspective; this is already where the game fails to live up the expectations it has set. In Lacanian psychoanalysis, a human being enters the so-called mirror stage around the age of four. This is when the child recognises itself as an individual subject and a potential object (of desire). This is caused by the child’s accession into the world of the symbolic. Language, signs, and codes structure the social world. An artificial logocentric understanding of how the world functions, which roles and duties a person has in society, and how to interact with other beings is imposed on the child. According to Lacan, this is when perception and thought are structured according to language and a chain of signifiers.

If that is the case, it would have been interesting to see how a child that predates this stage perceives the world. A world beyond imposed symbolic structure. How does a child perceive a world beyond symbolic logic, and how does it interact with this world without comprehending the physical conditions of causality? This game could have been trying to represent Kristeva’s idea of the Semiotic; being and existing through unarticulated drives before patriarchal symbolic order is imposed on our cognition. However, it failed in doing that.

The game manages to make the player see through the physical perspective of a two-year-old, but it misses to make us see a world that is stripped off the Symbolic. The kid may be tiny, little, and cannot talk, but it understands complex language structures, solves puzzles, follows advice by an eloquent teddy bear (Fig. 3) and remembers maze-like paths that enable it never to lose its way. Alternatively, to put it in other words, it is the player becoming the child’s cogito. The child is a vehicle to the player. So, we are not presented the perspective of a two-year old, but it is endorsed by our perspective.

Now, it may sound like a ridiculous demand to ask a developer to represent a perception beyond the Symbolic or causality. Nevertheless, it felt a bit disappointing that the game did not even try to approximate the bizarre domain of the Semiotic. I wonder how the game might have felt if all language heard in the game would sound like some gibberish or if non-Euclidean physics would have been used to represent a child’s perspective that does not know what causality is or how its basics work. It would have made no difference for the game and the player’s experience if the child had been aged between 4 and 10. However, precisely that expectation of seeing the world of a mute little kid was the game’s USP. A USP that has been shallowly fulfilled. However, the game was still praised on online fora for giving exactly that unique perspective. Yet, I may be so blunt to argue that many players have been fooled by the Disneyesque graphics that indicate a children’s world.

Nevertheless, one shall not forget that the aforementioned visual aesthetics, which one normatively associates with what a child considers appealing, are after all produced by an industry run by grownups. What we see in Among the Sleep is not a world through the eyes of an innocent child, but a world visually designed to extrapolate our western associations of how childhood should look like. In this sense, the game is closer to how an action figure from Toy Story’s perceives the world than to how a human child who predates the Mirror Stage might possibly experience a world that only slowly starts to make sense.

Nevertheless, the game itself is an inspiring and entertaining endeavour that fits well into the canon of good psychological horror games (for youths). There are of course countless other perspectives to consider when dealing with the game but what struck me while playing was the thought that I was not playing a two-year-old but a kid that was at least four. Its idea of presenting the perspective of a two-year-old has obviously outgrown the execution of the game. That is not a bad thing in itself. Yet, reading through the overall reception of the game on the internet makes me feel like the idea was nonetheless sold to most of the players, which can mean only two things. My demands towards game development are obscene and ridiculous, or no one has really noticed that the game does not sufficiently realise its own expectations.

Further Reads:

Butler, J. (1988). The Body Politics of Julia Kristeva. Hypatia, 3(3) 104-118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1988.tb00191.x

Lacan, J.-J. (1993). The seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book 3: The psychoses 1955–1956. (J.-A. Miller, Ed., & R. T. Grigg, Trans.) London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Lacan, J.-J. (1997). The seminar of Jacques Lacan: The four fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis (Book XI). (J.-A. Miller, Ed., & A. Sheridan, Trans.) London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Zizek, S. (2007). How to Read Lacan. London: W.W. Norton & Company.